Why Double 11 Stopped Working (And What To Do Instead)

There was a time when Double 11 was simple. One date. One promise. “Lowest price of the year.”

As 11.11 hits the clock, you’re ready to shop your favorite brands, slashing prices with amazing discounts, rushing to buy all of the good deals. You feel like a winner.

Fast forward to 2025, and the picture looks very different.

The festival now stretches from early October to mid-November, with overlapping pre-sales, “plus” events, and endless coupon ladders. GMV still grows roughly 1.7 trillion RMB this year, up from 1.44 trillion, but the growth rate is slowing, and the mood is described as “muted,” “cautious,” “value focused.”

Retailers push harder on promotions and incentives. Consumers research more before they spend.

Somewhere along the way, the game changed, and this year feels dangerously close to a breaking point.

This is The Last 11.11 Playbook: not because the festival disappears, but because brands can no longer afford to treat it as a one-night stunt. Especially in a country where shoppers are already retail pros.

How the hype started (and what it got right)

The original Double 11 formula was genius:

- A clear focal point. One day, one story, one simple call to action.

- A genuine deal moment. Platforms subsidised heavily; brands got volume and new users; shoppers actually did see real price breaks in many categories.

- A new ritual. “Stay up, check out, brag about your haul.” Commerce became culture.

For international brands, it was the easiest story to sell upstream:

“China has a national shopping day. We show up, discount hard, and watch the line go up.”

In that era, the math worked. Margins took a hit, but the story was about acquisition, market share, and learning the ecosystem.

The compounding effect: more platforms, more tricks, less clarity

Then the game got crowded.

- New players like Douyin and Kuaishou brought livestream commerce into the core of Double 11.

- Cross-border demand grew. Platforms pushed Double 11 overseas into 20+ markets.

- Pre-sales crept earlier and earlier, until the festival became a five-week marathon instead of a one-night sprint.

Every year added a new layer:

- Pre-pre-sale.

- Deposit periods.

- “Pay the balance” windows.

- Red envelope drops.

- Platform coupons.

- Brand coupons.

- Bank cards.

- Member clubs.

- Secret codes.

And with each new mechanic, two things happened:

- Sellers built for the game, not the shopper.

- List prices quietly crept up ahead of the festival, just to be “discounted” back to normal.

- Marketing budgets inflated to chase GMV headlines and buy placements that looked impressive on internal dashboards.

- Unit economics became something you checked after the festival, not before.

- Shoppers levelled up faster than the system.

- Guides teaching you how to “stack everything” and “time your order perfectly” are now their own content genre.

- Users compare Taobao vs JD vs Pinduoduo vs Douyin across weeks, channels, and devices.

- Tools and social groups track prices before, during, and after Double 11 to call out fake deals.

The more complex the game became, the more professional the players on the other side of the screen became.

China’s shoppers are retail pros. The game backfired.

This is the core truth that a lot of overseas boards still underestimate.

They know:

- How to spot inflated “before” prices.

- When a “limited time” discount quietly repeats next week.

- How to arbitrage across platforms, cross-border options, and even grey channels.

- How to wait out the noise and buy in the quiet windows when brands get desperate.

At the same time, macro realities: property pressure, wage stagnation, and youth unemployment, make shoppers more cautious and more value-driven. They still spend, but they spend like portfolio managers, not kids in a candy store.

The result?

- Margin compression for brands. You raise list prices to protect margin, then discount harder to keep up with the war around you. Net, you give away more than you planned.

- Trust erosion for consumers. Each “fake lowest price” makes the next story harder to believe.

- Signal loss for platforms. GMV is still huge, but so politically and competitively sensitive that major platforms now avoid publishing a single festival number at all.

Double 11 used to be the clearest signal of China’s consumption story. Now, even people inside the ecosystem are asking if the model itself is overheating.

2025 feels like a tipping point

Look at the 2025 pattern:

- The festival starts even earlier, on October 9, and runs past November 11.

- GMV grows, but the growth rate slows.

- Retailers rely on deeper discounts and heavier subsidies to move a more cautious consumer.

Behind closed doors, you hear the same stories:

- “We hit revenue targets, but we don’t know what we actually earned.”

- “We increased marketing spend because everyone else did.”

- “We discounted harder just to defend last year’s GMV line.”

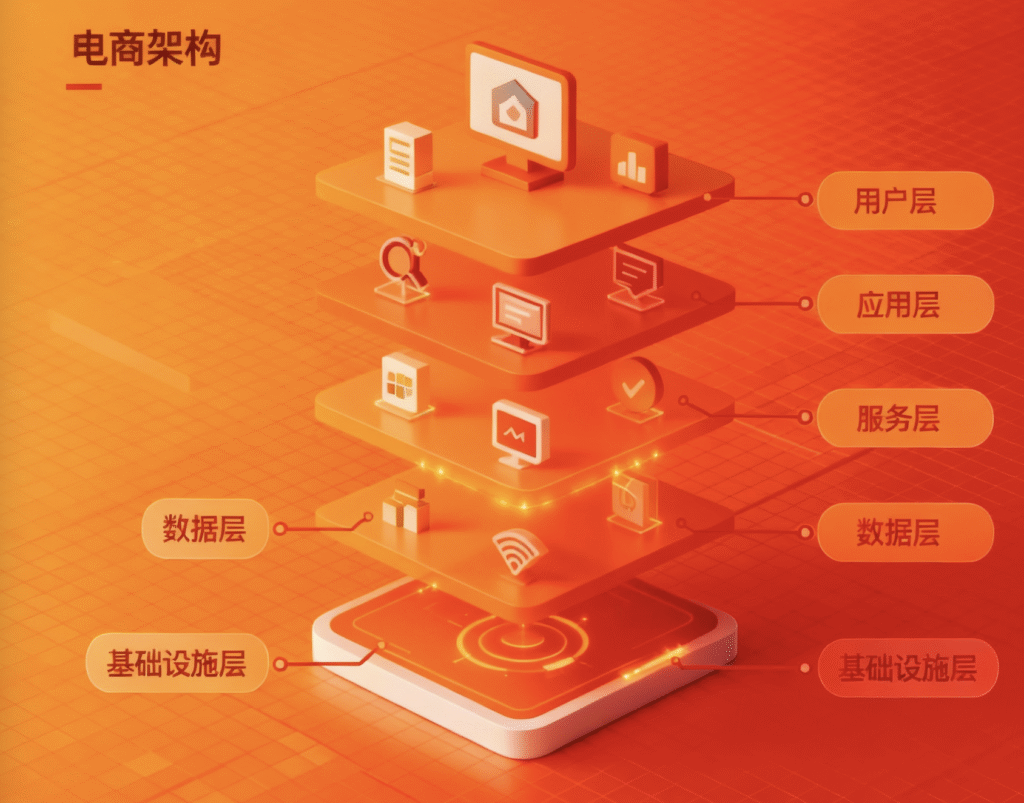

E-Commerce in China

Looking at China from the outside, Double 11 is no longer just a local shopping festival. It is an early view of how commerce behaves when AI is embedded in the stack and shoppers think like operators.

Three ideas to carry forward:

- Treat 11.11 as a stress test, not a one-off stunt. If something breaks in November, it was fragile all year.

- Build a creative and pricing system that can hold its shape while platforms, formats, and tools keep changing.

- Assume consumers will compare everything, and be the brand that rewards that intelligence with clear value and honest pricing.

This is what a game that is dragging everyone down looks like.

Not a crash. A grinding, exhausting equilibrium where no one wants to be the first to step out of the war.

Which is exactly why this is the right moment to declare your own Last 11.11 Playbook.